A Visit to the Food Museum's School Dinners Exhibition

What do you remember about your school dinners?

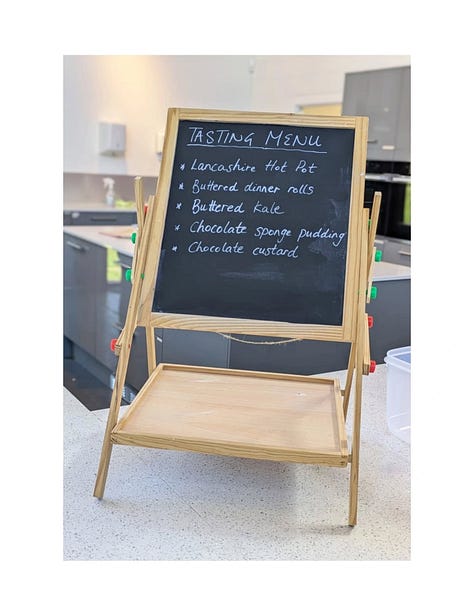

At yesterday’s School Dinners Exhibition launch at the Food Museum in Stowmarket, we were given little report cards and allocated to one of three dinner sittings. I noticed a gaggle of men in the queue so wrapped up in the experience they were moving about excitedly like the schoolboys they once were. It was unexpectedly moving. I felt myself regressing too; the school milk display made me feel quite angry as I remembered hour after hour of being made to sit in front of the milk I refused to drink. Lots of other attendees shared similar memories as we waited in line or browsed the exhibits. We sat on benches drinking lemon squash, water, or milk and eating Lancashire Hot Pot (lamb or vegetarian), dinner rolls, buttered kale, and a bowl of chocolate pudding with chocolate custard served by dinner ladies recruited from the museum’s cafe. Jeanette Orrey MBE, former dinner lady and co-founder of Food for Life, was also in attendance. The food was sustainably sourced.

I found the whole exhibition both nostalgic and forward-thinking. The Food Museum wants us to think about the political and sociocultural nature of school lunches and find ways of improving quality, ensuring all children are fed well at school. MP Sharon Hodgson, chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for School Food, opened the exhibition and spoke movingly about the stigma she experienced as a recipient of free school meals. She has long campaigned on the issue of equitable school meal provisions. "It’s an honour to have officially opened this unique exhibition and to celebrate the important role school meals have played in all of our lives,” she said. “Visitors to the Food Museum will relive childhood memories and stop to appreciate the care and attention that went into making their school dinners.”

Her speech made me think about England’s disdain for institutional or mass-catered food and how we seem to view it as sad food, for people devoid of other options, and have lost the fraternal, socialist principles that underpin mass-catering at its best (France was mentioned). During the Second World War, government-funded canteens known as National or British Restaurants, offering fixed-price value menus, opened. The V&A Museum had its own canteen. In France, bouillons were an established part of the Parisienne culinary scene, feeding thousands of hungry workers. (In March I visited the first one to open in Strasbourg, which I’ll write about in another newsletter.) The provision of affordable (which often means free) school meals that reflect local culture is critical if we are to reignite in the population a desire to protect quality mass catering from the cradle to the grave. That means schools, hospitals, places of work, and on the high street (an example: in the USA, Picadilly’s is a famous chain of affordable cafeterias).

Jenny Cousins, Director at the Food Museum, said, “School dinners are a shared experience that cut across generations, bringing back childhood memories of lunch lines, long tables, lumpy custard, and everything in between. Our School Dinners exhibition invites visitors to take part in a nostalgic journey, exploring the tastes, smells, and stories of the past. Visitors will hear from dinner ladies that have shaped school meals over the years, explore unique artefacts that bring them back to their school days, and can even tuck into a traditional school dinner as part of their experience,” she added.

“It also explores the serious side of school food. For some children, school dinners are a matter of choice. For others, they may be their only hot meal of the day. School meals are a flashpoint in an ongoing debate about poverty and the exhibition asks big questions about our values. Whose responsibility is it to feed children? How much help should the government give, and who should get it?”

The exhibits and staging are educative, playful and serious with some great touches: the checkered backdrops remind me of a maths exercise book, and the information is presented like a classroom display, using speech bubbles and colourful graphics. It reminded me of my master’s degree in health promotion and education, where learning styles were a big part of the syllabus. Big colourful graphics are a great way to impart serious health information.

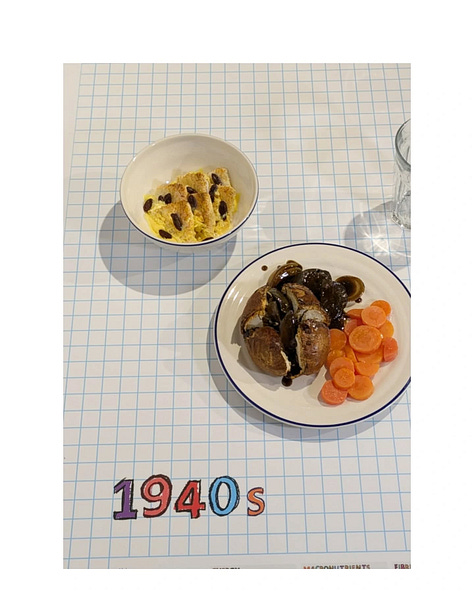

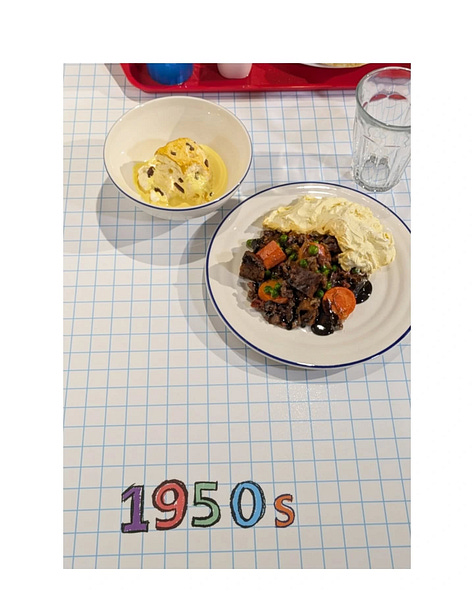

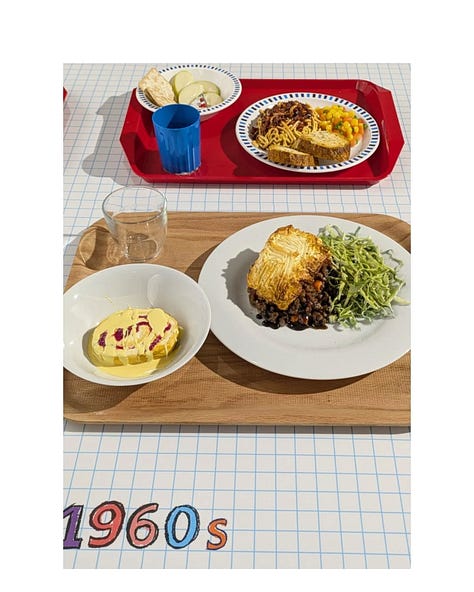

A display of school dinners across the decades using Japanese-style food models shows the transition from in-house cooked food to the prepackaged items of the nineties and early oughties. Today, menus are more eclectic and multicultural. Trays of food from the forties to the sixties look like something you'd order at St John. I was told Fridays remain the most popular day in school because fish and chips are usually offered. This is a part of British culture, especially if you are Catholic: it's traditional to abstain from meat on this day, and while we might have lost touch with its underlying history, we still do it.

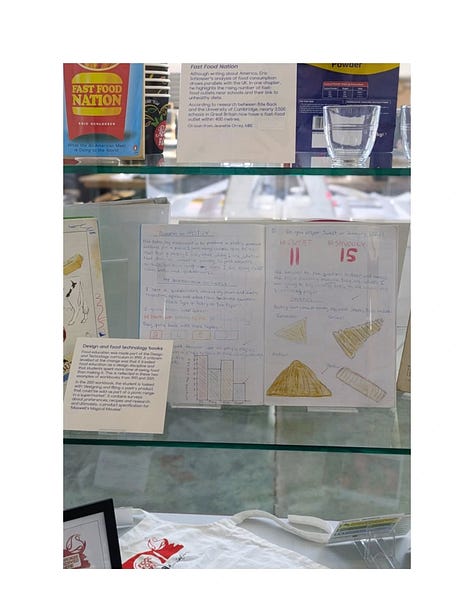

I loved the display cases filled with school lunch equipment: lunchboxes through the ages, different plates, and metal water jugs from the sixties and seventies, which are pretty cool now; I remember how we used to half-fill them with water and spin them until they careered off the table. There was a wall of comments by adults and children about their memories of school dinners. It reminded me of my son’s first school report, which had a space for him to write about his goals for the next school year underneath comments from his headteacher and form tutor. My son: “I want seconds at dinner more often.” His teacher told me the staff laughed their heads off at this; all the other pupils had opted for self-improvement.

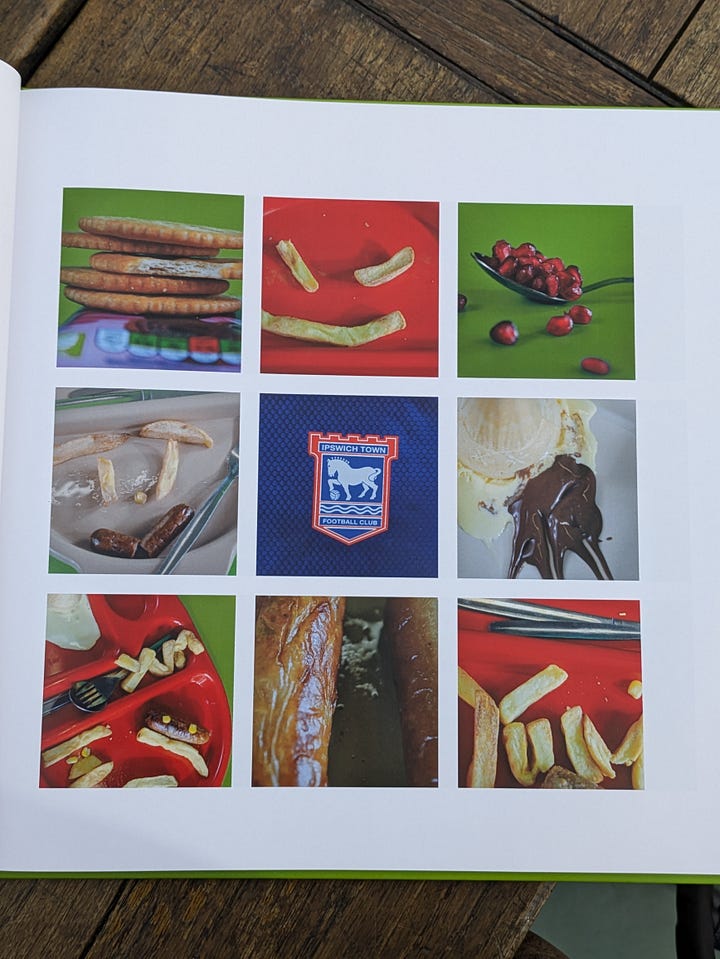

In a little corner of the exhibition, I found contributions from local schoolchildren about their lunches. (A special mention to Henry, who likes crisps and thinks about them in great depth, Izzy, who states if we are what we eat then she's a tuna sandwich, and Sarya whose contribution: "the jelly splash" is such a gorgeous piece of imagery.) The book is called ‘What I Ate For Lunch’ and was created as part of Jubilant 2024, held at the museum. Working with photographer Sadie Windscheffel-Clarke, students took photos of their school lunches (and they are amazing, like something you’d see in a Vittles photo essay) to accompany their thoughts about what they eat. I found it inspiring; it made me think about how I describe food, the actual shape my words make on the page, and why writing for an audience can cause one to be less spontaneous, playful and childlike. The museum worked with seven young curators, aged 16-24, who collaborated with museum professionals, academics, and food experts to research and develop the exhibition content, providing fresh perspectives.

More info:

The exhibition is thought to be the first of its kind in the UK.

Tasters in the first few months of the exhibition will be inspired by recipes and menus from the 1940s. Using historic menus from Norfolk schools, tasters will include Roly Poly, MeatLoaf, Egg Cheese and Bacon Pie or a sweet dishes like Rice and Raisins, Lemon Pudding, Spotted Dick and Treacle Tart. As well as changing specials in the café, groups can pre-book a 2-course, nostalgic school school-dinner-style meal specially curated for the exhibition. They can pick from three options across three decades:

School Dinner Menu:

1950s

Stewed beef. Jam roly-poly pudding. Glass of milk

1970s

Spam fritters. Rice pudding and jam. Flavoured milk.

1990s

Rectangular pizza, chips and sweetcorn. Sprinkle sponge pudding with pink custard. Orange squash.

The Food Museum has kindly offered its recipe for Chocolate Crunch, which I have reproduced here in its original form:

Chocolate Crunch recipe:

2 oz / 56g Margarine

2 oz / 56g Sugar

Vanilla Essence

1⁄2 tsp Cocoa

4oz / 115g Self Raising Flour

1 egg

Method:

Grease sandwich tin

Set oven to 175C/ 350F/ Gas 4

Melt margarine with vanilla essence in saucepan

Mix sugar cocoa and flour

Add to the melted fat and beat in egg

Press into greased tin

Brush with water

Sprinkle with sugar

Cook for 30 minutes

Information about the Food Museum:

The Food Museum, formerly the Museum of East Anglian Life, is a large 84-acre estate with 17 historic buildings, animals, gardens, a river walk and a collection of over 40,000 objects. Through exhibitions, activities, events and programmes, the museum seeks to engage visitors with where their food comes from and the communities that grow and make it. The museum is located in Stowmarket in East Anglia, known as ‘Britain’s Breadbasket’.

www.foodmuseum.org.uk/events/school-dinners/

Link to the Suffolk News story about the launch and the BBC report. You might see reports about the launch on BBC regional news and national breakfast programmes.

School Dinner Heaven: Nostalgic Recipes That Take You Back by Dorothy Spooner

Shahnaz Ahsan on the nostalgic power of school dinners.

BBC Bitesize: A Brief History of School Dinners.

A more in-depth look at political history and school dinners via History & Policy.org

The National Archives is a great resource.

If you don’t wish to take out a paid subscription but would like to contribute to my newsletter, I have a Ko-Fi page here. You can also take out a subscription via the button below.

What a great idea for museum exhibition! I enjoyed reading your summary. In Switzerland, public schools generally don't serve lunch. Kids usually eat at home or at another off-site program, and then return to school in the afternoon.

This looks like such a fascinating exhibition!