Organ meats can appear pretty visceral on the butchers’ slab, but we’ve never seen our own human equivalents in the flesh. Hence, there’s a corporeal disconnect on some level, making it easier to cook and eat some animal parts than others, irrespective of how they actually taste. But I’m not referring to that daft nonsense where culinary scalp-hunters go in search of the most outrageous and rarest meals so they can tell you all about it via Buzzfeed or Vice. This always seems to ‘other’ the food eaten in different regions, and I really don’t want to do that, but I know from experience that penis and virility jokes come thick and fast, no matter what country you are eating your organ in, so please forgive mine. The disgust so often expressed by diners is not polite — nor is it culturally appropriate — but the amusement and teasing of westerners abroad, by the people cooking and serving their food is warranted and understandable. They see us.

I first ate bulls penis (hwangsoui seong-gi 황소의 성기) in Busan in the early eighties when I was a teenager staying in this southern Korean seaside city where my father was working. Based at Haeundae Beach, where a smattering of international hotel guests was pandered to with tuna club sandwiches and neutered versions of local cuisine, I was constantly in trouble for roaming the streets, meeting local teenagers and playing hooky from the roster my parents had set. Starving hungry from hiking up Jangsan Mountain, where we’d dare each other to annoy the soldiers who patrolled the fenced-off minefields, I’d snub the hotel’s five restaurants, return to the town, and slurp up bowls of goodness knows what from the hawker stalls along the promenade.

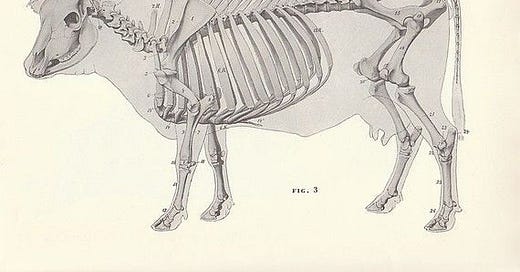

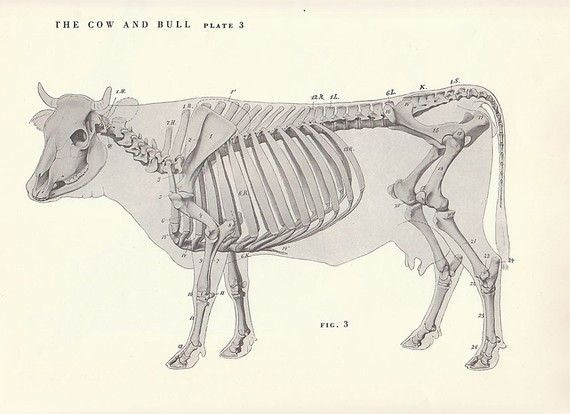

Having visited before, I was accustomed to eating meals where the ingredients were unfamiliar to me, and we were often invited into the homes of the locals my father worked with to eat. Still, that night the restaurant served bulls penis, and it wasn’t much of a challenge to identify what was on the menu. As we perched on a bench, sweating in the oppressive humidity of a late summer evening, what initially resembled snipped-up, flayed eel came into sharp focus. A bull’s penis can be more than two feet long and cooks usually split along its urethra then slice the two halves into thick coins: diners can expect to be presented with an organ whose tough visceral membrane has been removed; its insides rinsed as carefully as good chitlins are. Seen scaled up, you can appreciate a dick in all its hydraulic glory and marvel that erectile dysfunction isn’t more common in animals as well as humans. Mine still had part of its sigmoid flexure attached, and the entire organ had been sliced longitudinally then boiled in a tenderising chilli-infused stock before getting the hot coal treatment.

The dissection and boiling were bold, but fresh penile tissue will contract and shrivel up when it hits the heat of the coals, and without that tenderising bath, you’ll end up with an animal chew. As a prelude to the bulgogi, which was the main event, a pot of burning hot coals had already been slotted into a hole in the centre of the table, and five or six penes were placed inside special cages that resembled lacrosse sticks. These rested on the coals, and the basting sauce was mopped onto the meat using a brush with bristles as long as a hippies ponytail.

My penis wasn’t served with a garnish of culinary philosophy. There was no menu detailing the chef’s conversion to nose-to-tail eating, and the locals ordered, waited, then ate, and nobody patted themselves on the back for being daring. I didn’t feel adventurous; the only thing I will not eat, as a matter of course, is porridge no matter how artfully it is presented because it is the devil’s semen as far as I am concerned. The penile flesh was smokey hot, patched with char and packed a hefty bounce and fightback in the mouth. I chewed and chewed; I chewed some more, and then I swallowed. A good eater should always swallow.

As a kid, eating offal, innards, and dangly bits was something that I gave little thought to, but not because I was a massively over-privileged and precocious food brat. It was simply how we cooked and ate, probably because I was exposed to homely cooking in different parts of the world, and when I came back to the UK, I was less accustomed to the kinds of food other British children in my neighbourhood ate. It’s hard not to feel a certain loftiness about the nose to tail movement because thus it ever was with us. My Midlands relatives would certainly not think it appropriate to praise a child for eating black pudding, liver, tripe, scratchings and faggots, haslet, or cow heel in that affected way you see now, but we’d get a clip round the ear if we left any of it. Nor would my broad tastes be regarded as anything other than expected by the Mexican people who took my catholic appetites for granted because it was simply unthinkable for a small child to exert any control or influence over the family diet. This didn’t mean that they neglected our palates—far from it — but spiritual and religious attitudes towards nourishment and gratitude precluded fussiness.

Try turning down a bowl of Menudo after someone has slaughtered their animal, broke its carcass down, cleaned miles of intestines, then turned some of them into a soupy bowl of stew. Its eating was as communal as the slaughter, an act of reconciliation and thanks, driven by hunger and crowned by a sense of communal satiation. Waste was fiscally and morally unthinkable, and superstition came into it too. In northern Mexico, our housekeeper’s mother strongly believed that unnecessarily discarded leftovers, tossed carelessly on the ground ‘for the chickens’ would poison it for crops forevermore.” “Dios lo sabrá,” she’d scold me when I left a few scrapings on the plate and off she’d go to hunt down a scrap of tortilla to mop the plate with because the marriage of two leftovers in one meal turned it into a sacramental act.

I’ve enjoyed pots of chicken necks slow-braised then given a few minutes to blister under a grill, the flesh rubbed with aromatics for a final flourish, and assorted lights, viscera and skin of various critters have been fried, boiled, roasted and stewed then served up. Gelatinous pigs tails with blistered skin and soft-as-silk meat were served up on street corners by the small units where the Guadalajaran glass blowers plied their trade. Thrust into a charcoal brazier until they ran with fat, these bronzed little corkscrews were placed inside a corn husk to catch the scalding hot drippings. They are rhapsodic. If you’ve read Laura Ingalls Wilder, you’ll know this part of the pig is fought over and damn right it should be, but curly tails are far more fun for a child to eat than their straighter brethren (although better chefs than I have rhapsodised over the latter). Either way, the fact that the skin covering a pigs tail remains in place (unlike oxtail) means that each sticky-lipped bite contains a perfect ratio of skin to meat to partially broken down tendon and cartilage. Ask your butcher: they can get tails, necks and other bits for you, and they are usually super cheap.

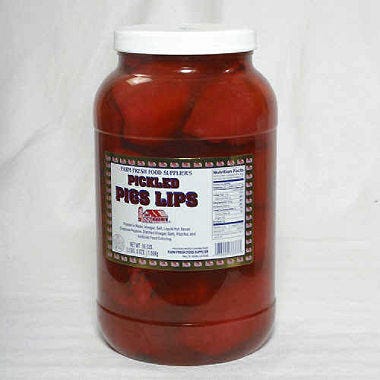

There’s plenty of porky adventuring still to be had in the classic Deep South; Mississippi and Louisiana especially. Stop at a country store and on the counter will most likely be opaque jars full of murky red liquid where pickled pigs lips float and bump against the plastic walls. (That red liquor they float in isn’t blood, by the way, it’s a red dye which, for some reason, is traditionally used.) Slightly bloated, (like all floating things are wont to be after a few days of immersion) they are less disturbing than you’d think in this age of plastic Hollywood trout pouts; try to imagine what Babe the Pig would look like after a few months wed to a Kardashian. Regarded as a classic dive bar snack in Louisiana and immortalised by rappers VP and Breezybee in their 2014 rap, “Pig lips, boudin and chips”, the eating of them is encoded within the DNA of many southerners who know how to create a tension between chaw and crunch by matching them bite for bite with the jagged shards of potato crisps. Bash the bag of chips on the counter first, then bung in the lips and give the bag a good old shake. It’s working-class panko, basically, and if you can bear the idea of a pickled egg inside a packet of crisps, this isn’t that much of a leap, truly.

Want to try lips? It’s not easy to buy them ready-pickled in the UK, but you can order online from the Pickled Store if you are US-based. These aren’t Johnny-Come-Lately pig lips, the Pickled Store says, so don’t mistake them for a postmodern version all lubed up with irony to allow them free passage through your gullet without the triggering of cultural and class insecurities. These haven’t been fiddled with by a young buck of a chef seeking to make their mark on the world by introducing a new crowd to a reinterpreted old faithful. Your gorge will have to cope with their defiantly unreconstructed nature. The company have been making their pigs lips to the same recipe since 1933, and their customer testimonials lay bare the love we all have for certain foods, no matter how peculiar they sound to others.

So will the nose to tail movement result in pigs lips moving out of the country store and gas station and onto our (higher-end) plates? Will ex-bankers running food trucks suddenly see the labial light? My money isn’t on bulls penes becoming the latest trailer snack in the UK, that’s for sure but pig lips and tails? They should be. The popularity of crispy pigs ears and porky heads on plates may have groomed us to eat the other facial features solo. And I’m definitely comfortable with betting £50 on the likelihood of barbecued pigs tails becoming more popular over here.

So, where else do they eat animal penes?

In Jamaica, cow cod soup is bull penis is stewed with bananas, rum and peppers and is used as an aphrodisiac.

In Bolivia, Caldo de Cardan is similar and is also a popular hangover cure. The soup takes its name because it is believed the penis of a bull is similar to a cars drive shaft. Lengthy braising (ten hours +) concentrates the broth and helps develop taurine, it is believed, before the beef, chicken and an entire lamb rib alongside the boiled egg, rice and potato are added.

Malaysians eat beef torpedo soup to increase male virility. The thick and spicy broth is spiced with fennel seeds, cinnamon, garlic, cloves, and diners can enhance the symbolic potency of the dish by building it up with more bones and tendons. Where to find it.

A North African recipe serves the penis cut cross-wise, scalded, skinned, drained, then boiled and sliced. Aromatics in the form of onions, garlic and coriander flavour the flesh as it is slow fried in oil and then added to vegetables, then braised for another couple of hours.

Yemeni Geed has chopped peppers, tomatoes and cumin and saffron added to the braise, and Yemenite Jews eat Gulasz z Penisa, a stew made with ram or bulls penis, too. Yemenite and Sabra Cooking by Naomi and Shimon Tzabar is out of print, but it does contain a recipe for boiled bulls or rams penis with coriander and garlic.

Fergus Henderson on pigs tail: “At other times I have sung the praises of how the pig's snout and belly both have that special lip sticking quality of fat and flesh merging, but this occurs in no part of the animal as wonderfully as on the tail. You must ask your butcher for long tails.” Here’s a recipe via The Caterer and an interview with Fergus in the LA Times.

Serious Eats on Menudo and glutinous foods. Not keen on the headline, though.

A recipe for a simple Zimbabwean chicken neck stew. And Catherine Phipps’ book, ‘Chicken’, is rare in that it also features a recipe in a book written by a Britisher.

More on pickled pigs lips.

(This piece was published on my old blog in a slightly different format.)

Gives an honorable approach to the saying “Eat a bag of dicks!” which is something I’d like to rakishly present as pastries for the next protest march!

Growing up in the Middle East, we ate what was set before us. Sheep's ball sandwiches were available at many sandwich shops in Beirut over 50 years ago. And of course shawarma is not the same without the fat of the fatty tail sheep.