"Crockett Johnson shows us that a crayon can create a world.” (Philip Nel)

Miss Thorne was my first teacher in the UK, and she was American. A flinty cliff of a New Englander, her long silver hair was swept into a ponytail and secured with a tooled leather clasp in the shape of the figure eight. She wore corduroy smocks, thick woollen tights and clogs. I thought she was about three hundred years old; she was probably no older than sixty-five.

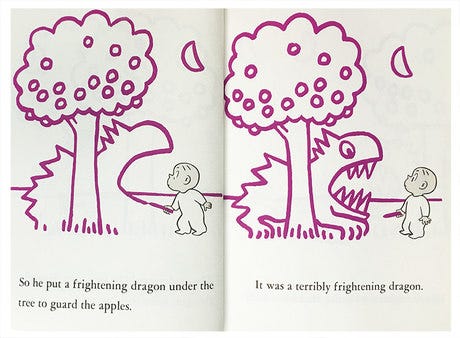

I told Miss Thorne about my favourite book, which had been left behind in Mexico and the next day, she gave me her copy. Back then, Crockett Johnson’s Harold and The Purple Crayon was relatively unknown in the UK. On a superficial level, it is a lovely, simple picture book with bold line drawings which jump off the page as they tell the story of a sweet baby and his adventures. On the other hand, Harold and The Purple Crayon serve as a metaphor for childhood and for growing up, dealing as it does with so many childhood challenges and fears.

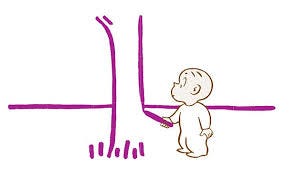

We see Harold has scribbled meaninglessly across the flyleaf and title page upon opening the book. Still, as we read the first line of text, “One evening, after thinking it over for some time, Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight,” the baby’s crooked and meandering scribbles become a purposeful straight line from left to right, mirroring the English language. Harold is the embodiment of the art of drawing, something the artist Paul Klee describes as “taking a line for a walk.”

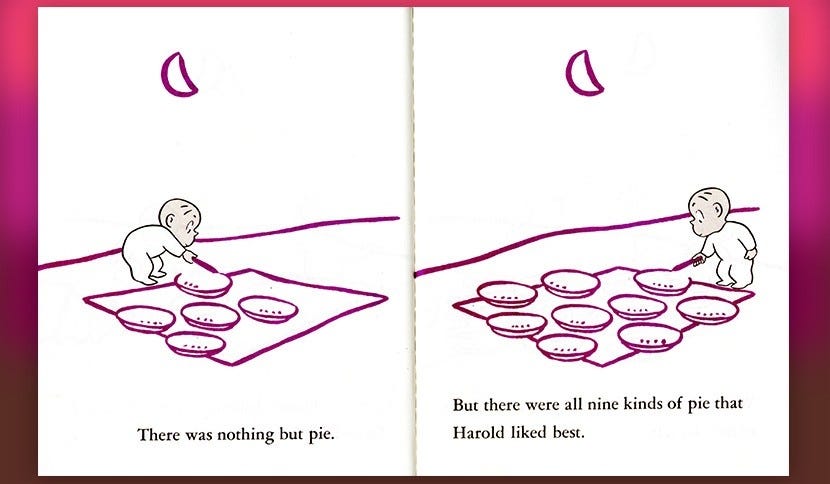

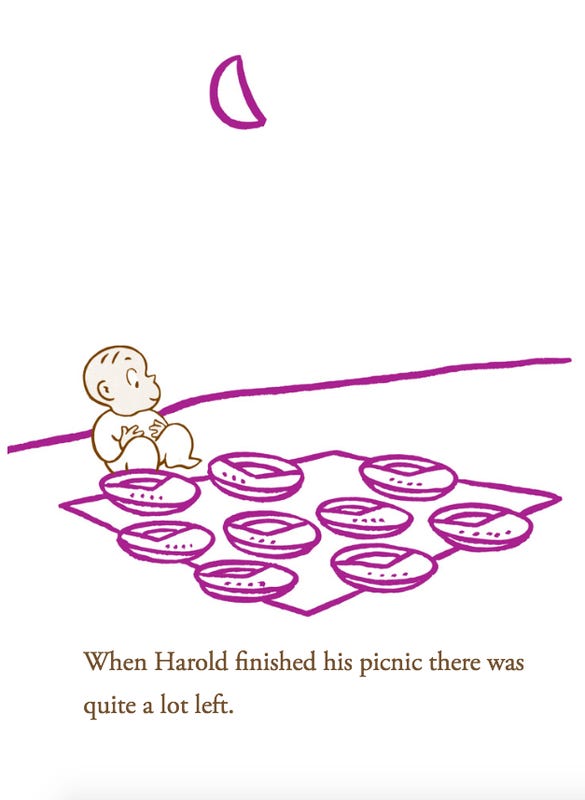

None of this mattered to the childhood me because all I cared about was the pies- all nine of them, even if I didn’t know what a pie was back then. The chance to sit down with an extremely hungry moose and porcupine and share a moonlit picnic with food that one had magicked from thin air with a single crayon was deeply alluring. The nighttime picnic is whimsically childlike in its depiction, embodying every imaginative make-believe tea party I have ever had but, to me, it spoke of future adulthood where I could create nine pies and sit down and eat them with whoever I liked. I could have a slice from each. I wouldn’t have to eat them all up, and if no hungry dog were hiding under the table to whom one might pass unwanted scraps whilst pretending to eat them oneself, then a porcupine and moose standing boldly beside me would have to do instead.

We didn’t bake pies in Mexico; a pie was alluring and exotic, and I don’t remember eating one until I returned to the UK. It was in my grandmother’s kitchen that I made pies acquaintance as I watched her turn flour, lard, salt and water into a malleable dough to be rolled out and filled with apples during that first winter when we lived with my grandparents. We read ‘Harold’ and discussed what flavours our nine pies might be. Her pies were circular like Harold’s and strangely and immediately familiar. To this day, every double-crust pie I bake must be round. Whenever I bake one, I think of Harold, what it means to be real, and how something becomes real. Living so far away from my grandparents in England meant they existed only in my imagination, much like Harold’s pies did in Mexico. The early years, of which I remembered nothing but about which I came to be told everything, seemed unreal. Must we experience things to be ‘real’, or can they simply exist in our minds? What happens when we manifest them? These questions form the crux of Crockett Johnson’s book.

Harold has to manage himself when night-time separates him from his parents, and he roams far from the safety of his bed. The fact that he has to problem-solve without their assistance is critical. Imagination has carried him far from home, and it will help him find his way back, equipped with new skills. When Harold awakes and notices that the moon has mysteriously disappeared, he draws one because he needs to make tangible something both mystical and mysterious and of substantial, practical importance, too: moonlight will help him navigate the darkness. When Harold tumbles into the ocean he has just sketched, he swiftly draws himself a boat. His actions lead to possible danger, but he is on the threshold of a longer journey- one that will teach him that eliminating risk and change is not the answer; what is critical is how we manage and react to it.

For a while, I no longer knew where home was. I was back on the cold, wintry and grey island of my birth, but little about it felt familiar. But over time, Miss Thorne stopped speaking to me in rudimentary Spanish, and I began to understand English; I made pies, steamed pudding and crumbles instead of flan and biscochos. I acclimated; I drew myself a different life.

Buy ‘Harold’ from Daunt books (Not an affiliate link.)

Read Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature by Philip Nel.

More on pie, by me.

In the dead of winter a night picnic sounds truly like a fairy tale.

Such a beautiful newsletter today. I too, like you and many others, have drawn different and new lives.