In 2021, I Am An Immigrant asked Ian the Painter to honour Marino Escobar, a New Orleans icon known locally as The Tamale Man. Marino left Guatemala for California over twelve years ago and moved to New Orleans after spending a few months in the Golden State. His sales call — different combinations of “Hot tamales baybeee”, “I love you baybeee”, and “I love you all my life” —reverberates around the narrow crowded streets of the Quarter.

I was swifter than Gwyneth Paltrow’s credit card in Loro Piana when I heard Marino’s shout on my way to the Golden Lantern. I think we’d just returned from City Park, where I’d fed a large proportion of my lunch to a gang of adorably persistent Ibis. I was hungry. And there he was on the corner of Royal and Dumaine, a wheely case filled with banana husk-wrapped and foil-swaddled tamales by his side. He was wearing his hat and gold chains as he did his best to persuade a group of jocks and their partners to buy his food. The bundles were as hot as the sun, and Marino winced as he retrieved them. I bought five. He seemed shocked. “De verdad quieres cinco?” he asked. “Los adoro, son raros en el Reino Unido. Tengo que hacer tamales en casa; y sola.” His face folded into a moue of sympathy and horror at my plight. "Te amaré toda mi vida," I told him. He laughed and gave me a hug before deafening me with one last "I love you, baybeee!" -something he says to all the girls and boys. (Apologies for my appalling written Spanish.)

Later that evening, I browsed Reddit and was struck by posts complaining about the price of Marino’s tamales. They are $5 each and LARGE. I paid $25 for five, and they lasted me three days, even coming with us on the drive down to New Iberia. I could have bartered for a discount but fuck that: I know how much work goes into making a single tamal/tamalli. They are not fast food. In comparison, you’ll pay between $10-$18 for a large Po’ Boy, which- like a tamal- is ingredients stuffed into a carb and served with sauce and garnish.

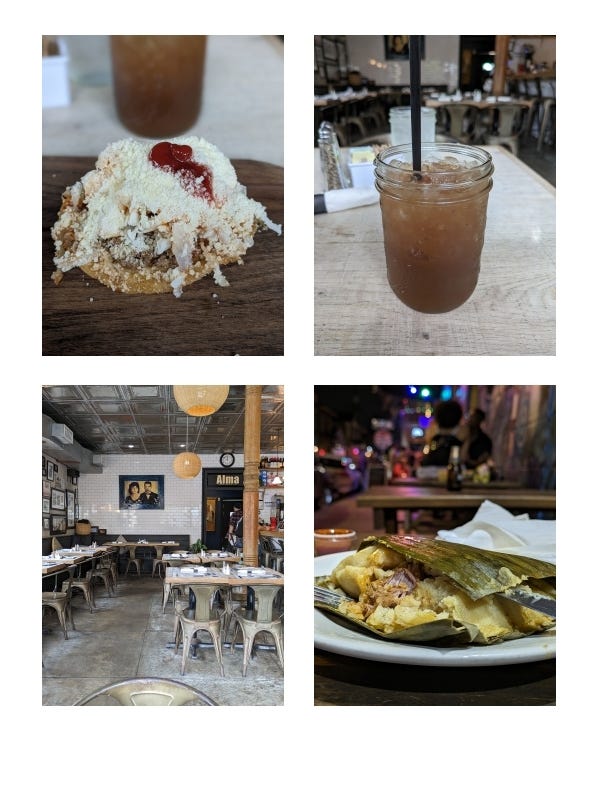

Buying tamales on the street remains my favourite method of acquisition because it feels deeply familiar. They hit differently. And Marino’s are decent enough: comforting, absolutely huge and emitting enormous corn-scented clouds of steam as you part the banana husk to reveal fluffy masa filled with chunks of chicken. They aren’t the best tamales I have ever eaten (for a start, I am a corn husk woman), but they do just fine, and I don’t mean solely in an emergency.

Tamales aren’t new to the city. The New Orleans-style hot tamal (which, being simmered instead of steamed, made with cornmeal rather than masa and served swimming in tomato sauce, is much wetter) gained popularity among the city’s non-Latin residents from the 1920s onwards when Bernardo Villafuerte Hernandez began selling tamales from the kitchen of a restaurant on the corner of Bourbon and Saint Ann. Hernandez went on to open El Ranchito, the first restaurant in the city to cook only Mexican cuisine. He was followed in 1933 by Mexican-born Manuel Hernandez (no relation), whose pitch was at the corner of Carrollton and Canal. That little cart helped finance a multi-location business until Katrina flooded his stores out of existence, which feels horribly ironic.

The influence of migrants from Mexico, Central and South America on the food culture of New Orleans is obvious in 2023. Many came post-Katrina to rebuild the city after it lost nearly half of its previously resident construction workers to floods, evacuation and/or permanent displacement. Between August to September 2005, the number of workers employed in construction and related industries in the New Orleans metropolitan area dropped from 40,100 to 22,500. On September 6, the Department of Homeland Security announced that it was suspending a number of pre-existing labour regulations for a forty-five-day period to accommodate survivors who had lost identity documents in the storm. During that time, employers would not be required to confirm employee identity and eligibility documents to federal authorities. Two days later, the Department of Labour lifted wage restrictions for a period of two months, allowing contractors working on federally-funded construction projects to pay their employees below existing federal wage standards. The predictable abuse of these workers did not take long to establish itself. Inadequate accommodation and safety equipment, wage theft, poor access to city amenities, and unmanaged construction sites led to gross breaches of health and safety- including lead and asbestos exposure- and a lowering of wages from pre-Katrina levels on top of the notoriously unaccountable nature of the city’s government created a climate of exploitation that lingers to this day.

Marino arrived some years after Katrina, moving into a city whose Latino population had been busy establishing businesses catering to their needs, following in the footsteps of the Vietnamese who moved to the city in their thousands after the fall of Saigon. (Viet-Creole and Viet-Cajun cuisine is pretty much established as a regional sub-speciality.) From the pivoting of existing businesses to cater to their new customer base, stocking products like Bimbo bread from Mexico and filling their king cakes with guava, to the slow and steady proliferation of bars, trucks, cafes and restaurants that are wholly Latino-owned selling the food they grew up with, the change in the city between 2019 (my last pre-pandemic visit) and 2023, is evident.

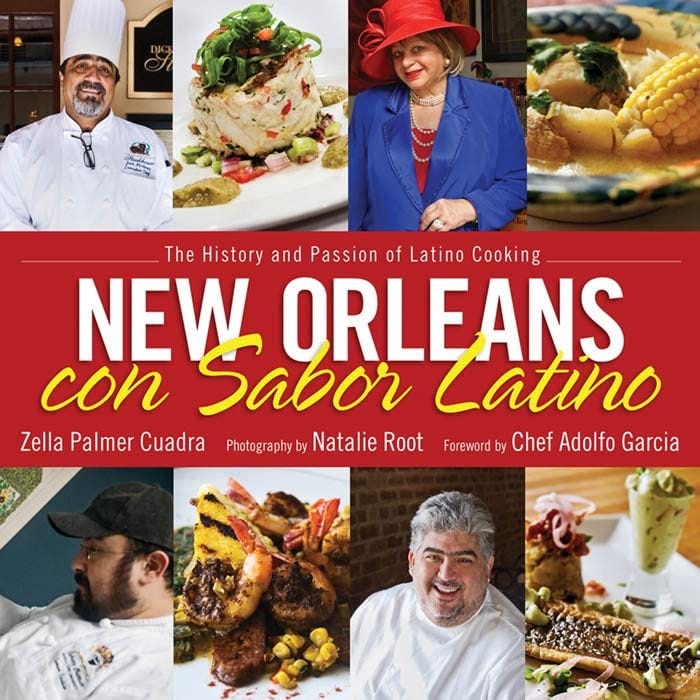

This time, I was spoilt for choice regarding Latino food in a city historically lacking in this department - despite Louisiana’s proximity to Texas. I could eat at all price points and see the evidence of cultural cross-pollination in menus where tortillas, sopas and arepas are paired with pepper jack cheese or boudin; cochon hot tamales are served with head cheese debris, tomatillo salsa and queso Guerrero; crawfish grits are given a little poblano heat; burgers are served Honduran-style; and mixologists and bartenders create cocktails that marry Latino and Louisianan ingredients and formulations. More Latino chefs work at a high level in the brigades of older, more traditional Louisianan restaurants. Some specialise in cooking traditional food from their own culture and are celebrated for this, but progress is also measured by how many Latino chefs and businesses are recognised as masters of innovation in their respective cuisines, receiving plaudits and bums on seats for doing so.

I’ve compiled a list of places to eat if you want to try Latino food (and tamales in particular) in New Orleans, plus a reading list for those who wish to know more about the taxonomy of tamales across the Americas. I have tried to include as many Latino-owned or run places as I can: always drink from the headwaters whenever possible.

Here’s some Facebook footage of Marino dancing with the Baby Dolls - and his wheeled case - outside the Jazz Museum. Do watch it; you'll hear his call—es tan alegre. He’s celebrated on Tiktok, too.

Where to eat

(Check opening times, which can be subject to change)

Arts District

Bésame (Latina tapas)

Broadmoor

El Pavo Real (Mexican)

Bywater & Marigny

Acamaya (Mexican mariscos-style menu of hot and cold seafood from James Beard award-nominated Ana Castro)

Cafe Alma (Honduran, beautiful tamarindo agua fresca, breakfast and lunch plates; I love the baleadas)

Cafe Negril (Honduran-style tamales plus tacos, gorditas)

Favela Chic (Honduran-style tamales, pasteles, good for late-night hunger pangs on Frenchmen St)

Galaxie (Mexican-style cocktails, tacos, fat tortas)

Taqueria La Coyota (Mexican food truck parked on St Claude Avenue)

Central City

Maïs Arepas (Colombian arepas beautifully styled and cooked)

East Carrollton

Taco Loco (traditional Mexican, meaty)

Faubourg Lafayette

Casa Borrega (Trad small Mexican menu and mezcaleria)

Taqueria DF (Food truck, their baleadas are amazing)

Freret

High Hat (Delta Hot Tamales)

Sarita’s Grill (Mexican and Cuban)

Gretna

Mangu (Dominican Republic)

Kenner

Williams Boulevard, between Veterans and West Esplanade, is where you’ll find a cluster of Latina-owned food businesses—Que Pasa’s digital guide lists Kenner-based establishments and other Latino places throughout the city. I like Sabor Latino, La Cocina for Honduran food, Fiesta Latina, Mi Pueblito at 3803 Florida, and NolaNico for Nicaraguan food. There’s a CBD location too.

Lower Garden District and Garden District

Lengua Madre (Modern Mexican tasting menu based on traditional techniques and ingredients)

Mayas (Pan-continental dishes made with ingredients common to Latin America; try the sesame soft-shell crab, vuelve a la vida, a lime-infused seafood broth, and the ropa vieja)

Metairie

Casa Garcia (Mexican)

Guillorys Deli and Tamales (Nola hot tamales)

Mawi Tortilleria (Yuca con chicharron, pupusas, fresh tortillas, Salvadorean breakfasts, Louisiana-influenced birria)

Lakeview

El Gato Negra (Michoacan cuisine)

Riverbend

La Macarena Pupuseria & Latin Cafe (Lots of vegan and vegetarian options, try the ropa vieja too)

Leonidas

Panchita’s Mexican Criolla Cuisine (Specialises in the cuisine of Veracruz)

NOLA Tamales (various locations)

Lower Ninth

Taqueria La Coyota (Food truck)

Mid-City

El Rinconcito (Bar with pool and a small menu very close to Taqueria Guerrero)

Normas Nola (Bakery, deli, party catering, and Latin food sales)

Taqueria Guerrero (Trad Mexican comfort food; some Central and South American)

Uptown

Como Arepas (Venezuelan)

Taqueria Corona (Mexican with American influences)

Warehouse District

Espirito (Regional modern Mexican)

Johnny Sanchez (Mexican with modern Louisianan influences)

West Bank

Old Style Hot Tamales (various locations)

Taqueria Sanchez (Little hut at 46 Westbank Expy, Gretna, selling mainly Mexican food)

City-wide

Crunchy Munchy Nola (Hot tamales, DM for info)

Holly’s Tamales (Based in Lafayette, delivers in and around Nola)

La Cocinita Food Truck (and soon to open a Venezuelan restaurant at 4920 Prytania Street)

Ollie’s Tamales (Hot tamales at various farmer’s markets)

Taceaux Loceaux (Truck, tacos)

Reading

José R. Ralat writes about the extraordinary diversity of tamales for Texas Monthly.

Megan Braden-Perry on the history of New Orleans tamales.

Todd A. Price wrote about Po’ Boys' prices in 2016.

Eva Sandoval on the Guatemalan tamal for BBC Travel.

Paches, a different kind of Guatemalan tamal.

Jackie Ann writes about Guillory’s Tamales for Our State Magazine.

A Berkeley research paper about Latino workers and human rights post-Katrina.

Freedom United on forced labour in New Orleans, post-Katrina.

I’ve written about Mexican tamales before.

And here’s a Nola/Louisiana-themed list of cookbooks recommended by Kitchen Witch (now sadly closed)

Adán Medrano’s twist on gumbo.

Central American Folklore in New Orleans by Shana Walton.

Brett Martin for Garden & Gun on the delicious food found in the city suburbs. (Includes some of the places on my list.)

Gustavo Arellano writes about the Nuevo South for Southern Foodways Alliance.

An old NPR article about the establishment of ‘Little Honduras’ in the city.

Hopefully the Que Pasa Fest will return to Lafreniere Park in 2025.

Visit

The Helis Foundation Enrique Alférez Sculpture Garden

Monument Tributo a los Trabajadores Latinoamericanos by Franco Alessandrini in Crescent Park.

Benito Juárez Monument in Garden of the Americas, Tremé.

I've been homesick for Marino's handiwork (and a bunch of other hotspots on your list) since moving away from New Orleans last year - thanks for the nostalgia and incredible rundown!

Central American tamales are very different than Mexican tamales. Guatemalans cook the masa like a porridge before assembling the tamal, while the Mexican tamal's masa is beaten raw with lard and broth before being wrapped around a filling and in a corn husk, or in a banana leaf in Oaxaca. Both types are steamed, but the Mexican tamal comes out fluffy and tender, where the Guatemalan tamal is custard-like and firm. Make Mine Mexican, please!