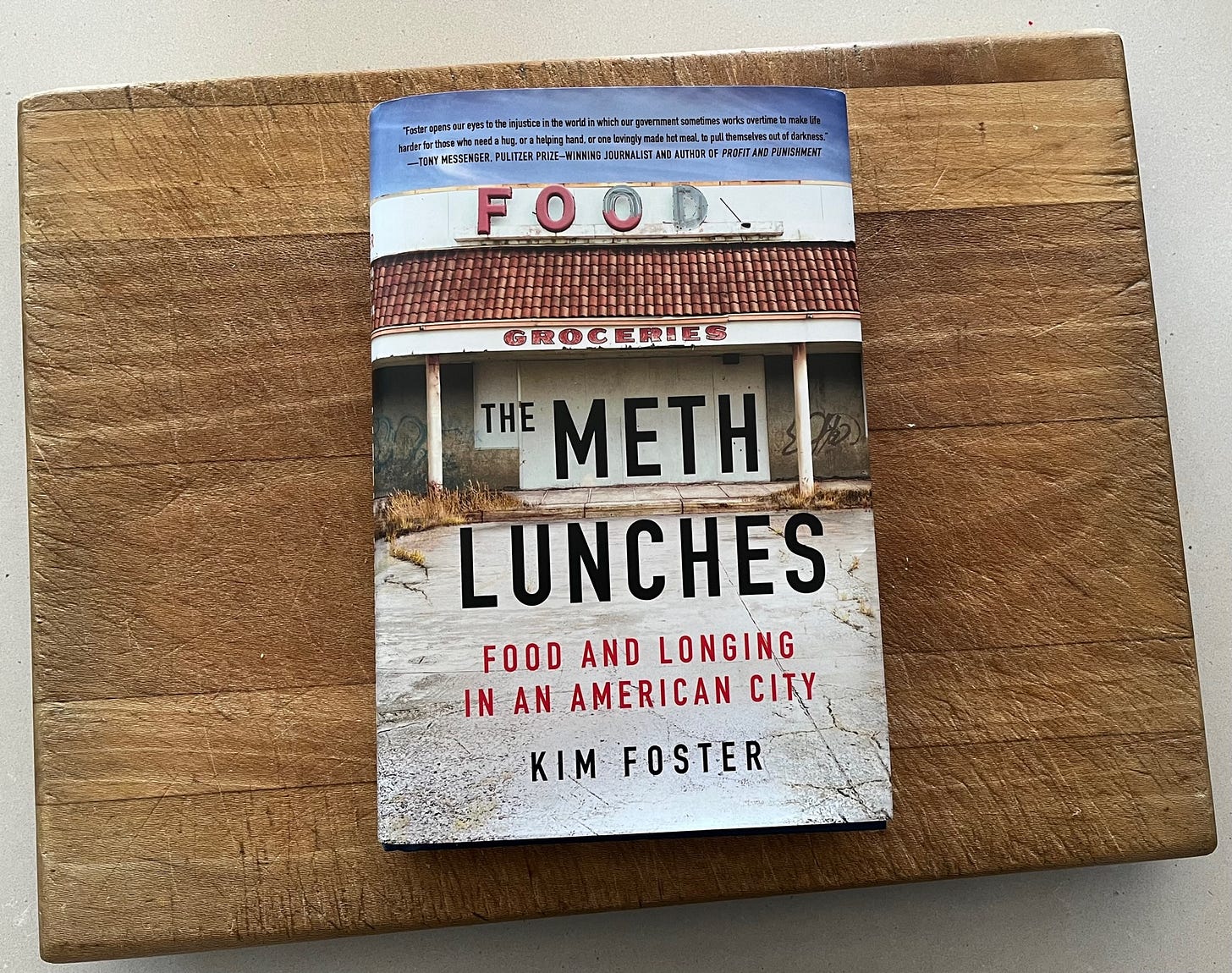

The Best Book on Food I Read This Year

Kim Foster’s The Meth Lunches is beautiful, harsh, and unforgettable.

Why isn’t The Meth Lunches at the top of every list of the best narrative food books of 2023? Kim Foster’s memoir of food and hunger in Las Vegas is bracing and tragic, infuriating and hopeful. She takes us into the lives of the unhoused; addicts who use, or stay trapped within a maze of recovery and slide; kids in a foster parenting system stacked against biological moms in poverty; the working poor, housed in beat-up roach motels that charge predatory rates by the week. Foster is a beautiful writer who uses her voice to scream about the inequities of a system designed to trap poor people in cages of need and struggle: essentially enslaving them, to exploit for the profit and comfort of the better off—for us. And yet this is also a book about gorgeous food, stunning in a yeah-that’s-right-bitches-look-at-me social media way; a way that triggers our bourgeois foodie hunger for hyper-flexed hedonics with little or no context.

And this contrast between poverty and the richness of Foster’s table opens up this mad chasm. I’m not sure if Foster does this to shame the reader or because she needs this food in her life to stay sane, or hopeful; to keep from giving in to the despair that settles on everything in off-The-Strip Vegas like Mojave dust on a black SUV. In The Meth Lunches’ startling cold open, an addict has blacked out in Foster’s backyard casita, and one of Foster’s kids is freaking out, thinking he’s died. A few lines later, Foster, her husband, David, and the kids go on as usual with the lunch Foster’s prepared. “This should be weird,” she writes. “It’s remarkably not.” She describes what they all eat, in prose that could be pulled directly from Eater’s 38 Essential Restaurants in, well, anywhere. Their favorite sukiyaki for the kids, and for her and David, “a pan of bacalhau no forno à portuguesa, salt cod baked on top of thin wafers of potato, onions, peppers, briny olives, blistered with cherry tomatoes, and charred lemon halves that get squirted warm and tart over the fish. We eat and talk about this dude like he isn’t passed out in our backyard.”

Foster’s world is crazy and chaotic, honest and intimate, and searing in its judgment of who we are, collectively, as capitalists; as progressives who claim to care about social and economic justice but still get our barista-formula oat milk and Tony’s Chocolonely bars picked and delivered from Whole Foods by some underpaid gig worker who might be living in the car they use to drop off our goodies; someone we can’t be bothered to see or acknowledge the humanity of. Foster has so much heart it’s messy, extravagantly too much. Like somebody you meet at a party who bypasses chitchat to talk earnestly about what’s fucked up in the world, and how it’s all on us to do something, and meanwhile you feel the heat of their body, they’re standing so close to you. Because they believe so passionately about what they’re saying, they forget the social rules of personal space. You smell their skin.

In 2017, Foster’s essay “The Meth Lunches” appeared in Desert Companion, Las Vegas’s NPR-affiliate magazine. The piece landed: racked up a James Beard nomination and appeared in an anthology of notable writing on food. A revised version is the opening chapter of Foster’s book. After decades in New York, the family moves to Vegas for David’s work. They buy a house in an older neighborhood east of the Vegas Strip and hire a day-labor construction hand, Charlie (the guy who blacks out in their backyard), to help with renovations. Charlie’s addicted to meth. Over the months that Charlie shows up for work, he uses, gets sober, and binges again. His wife, Tessie, uses too. They face eviction, an almost constant level of chaos. “Their lives,” Foster writes, “are a tedious wreckage.”

The thing is, Charlie becomes part of the family. Every day, Kim cooks a vivid, sprawling, gorgeous lunch for David, Charlie, herself, and the girls, and serves it family-style on the patio.

And you think the narrative is going to be that good, delicious, impeccably sourced and cooked food will Charlie and Tessie; that it will fix their addiction by showing them what’s possible, in some Michael Pollan fantasy of Berkeley, when people come together around the table, but of course it doesn’t. “Food is not love,” Foster writes. “Turns out that feeding people is love. Not the food itself. Love is the act of feeding someone.”

Foster perseveres with the act of feeding people even though our capitalist system of exploitation makes easy resolutions damn near impossible. The second half of The Meth Lunches chronicles Foster’s determination to keep a free food pantry going in her front yard for the first year of Covid. It’s messy and full of moral compromises, broken boundaries, self-delusions, and the limits of her own saviorism. Does Foster have the right to tell a meth addict that she can’t raid the pantry of all the meat, when she knows the woman’s going to sell it to buy drugs? “I want that meat to go to someone who deserves to have it,” Foster says. “What does this even mean—to deserve food? And I know this makes me the asshole. Fuck.”

If you’ve been missing Anthony Bourdain’s raw humanity—an intelligence that cuts through the lies we tell ourselves about the power of cooking, while never losing faith that food can make the world better but only if we rethink the parameters of “community”—check out Kim Foster. #