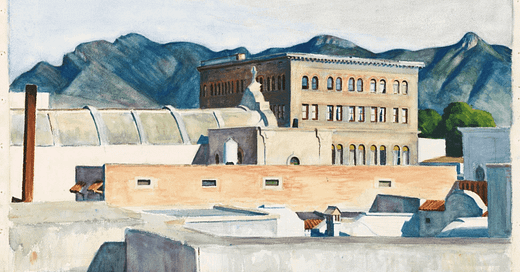

A long time ago, I wrote a short piece on Edward Hopper and his connection to Northern Mexico. It was published on a now-dormant blog. I’ve wanted to improve and expand upon my original thoughts for …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Topographic Kitchens to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.