I’m working on a longer piece about Queer Food, a new book by

but wanted to say a quick ‘hi’ and tell you about some of the things I have been up to. This post is too long for email and you will have to click on the link to read it all.In this month's Waitrose Food Magazine, I've written about my collection of fridge magnets, the principles that guide my collecting, and what recent research has to say about their emotional, recollective value. When I posted a link to my piece via Blusky, people sent me photos of their collections and told me about their favourites. It’s lovely.

These are my newest magnets, bought in Santorini.

They aren't quirky or unusual, but I love their colours and chonky little shapes. ( The round ones are painted pebbles.) I particularly wanted a windmill magnet, although I had only seen these austerely simple and beautiful buildings from the window of a bus. The tomato can magnet came from Vlichada's Industrial Tomato Museum, where they celebrate the island's PDO tomataki. The best experience we had on Santorini was our visit to this visually arresting place, whose restored chimney can be seen from miles away. We’d caught the jaunty open-sided ‘Fun Train’ in touristy Perissa and trundled our way along the seafront listening to piped eighties pop music before turning inland to be blasted by the island’s famous pumice-laden winds, a scrub treatment that some spas charge hundreds of pounds for. After a vertiginous descent to the marina in Vlichada, we disembarked and walked the few metres to the museum.

The tomatoes used to be washed with seawater that had been pumped in from the Aegean just feet away from the buildings. I had seen small tomato plants almost devoid of foliage planted on pockets of land beset by dust devils whose soil was bone-white and so dry I could scarcely believe it capable of nourishing any life at all. Rainfall on Santorini is extremely low, and farmers cannot — and do not — water their crops, having adopted through necessity, a traditional low-input cultivation system. This includes the planting of nitrogen-fixers like barley and lentils. These tiny tomatoes with thick skins, high acidity and sugar levels from the intense Cycladic sun are anhydrous (waterless), relying on dew and atmospheric humidity retained in the island’s porous pumice soils, whose high salt levels trap and hold atmospheric water: “The plants are under conditions of water stress, and this, together with the alkaline soil, gives the product special characteristics,” says the document from the EU designating the Santorini tomato as a PDO in 2013.

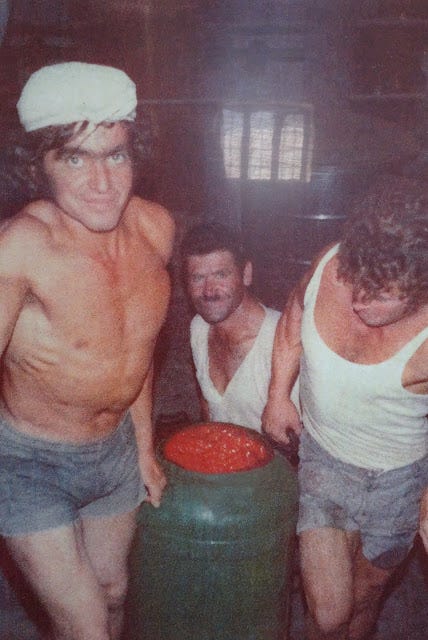

Despite the tomato’s genetic resistance to black mould and powdery mildew, cultivation has at times been as rocky as its island home. When the factory opened, it had to generate its electricity as Santorini had no national grid (the old coal-powered boilers are on display). Farmers had to transport their tomato crops on donkeys and mules across an arid landscape almost devoid of shade. Many former employees made a 7km round-trip journey to the factory every day to work 12-hour shifts during the harvest. It was hard, exhausting and hot, but audiovisual testimonies from former workers and farmers describe the factory’s important role as a community space where people from isolated parts of the island could meet and catch up with their peers. A member of staff at the museum tells me about Antonis Valvis who began working at the plant aged seven and was eventually sent to university to train as an engineer, paid for by the Nomikos family. He became head of maintenance and continues to make daily visits, post-retirement.

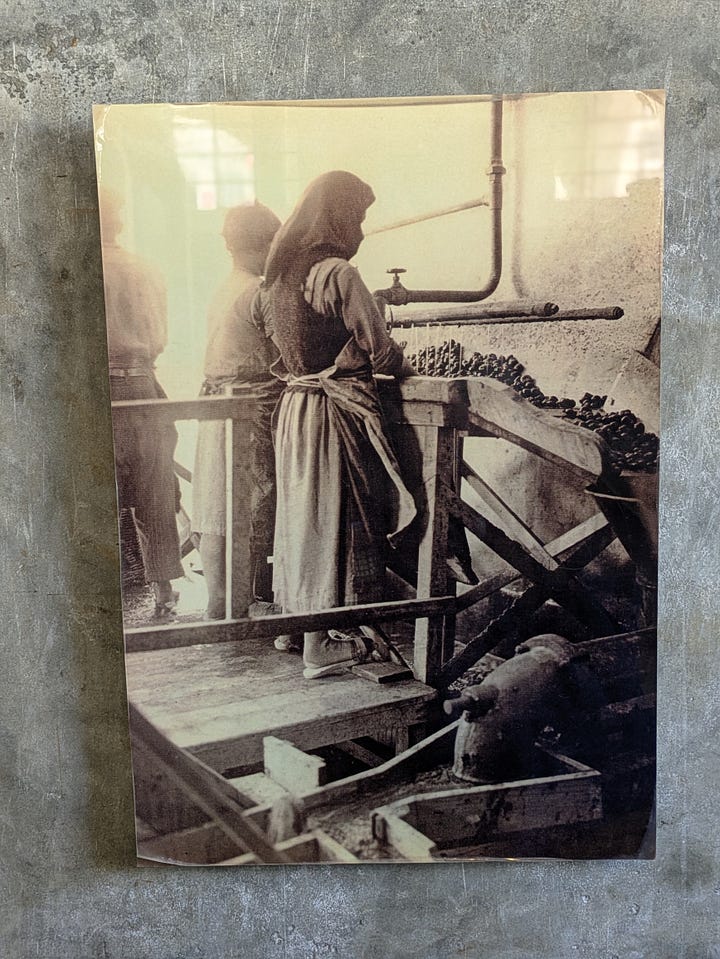

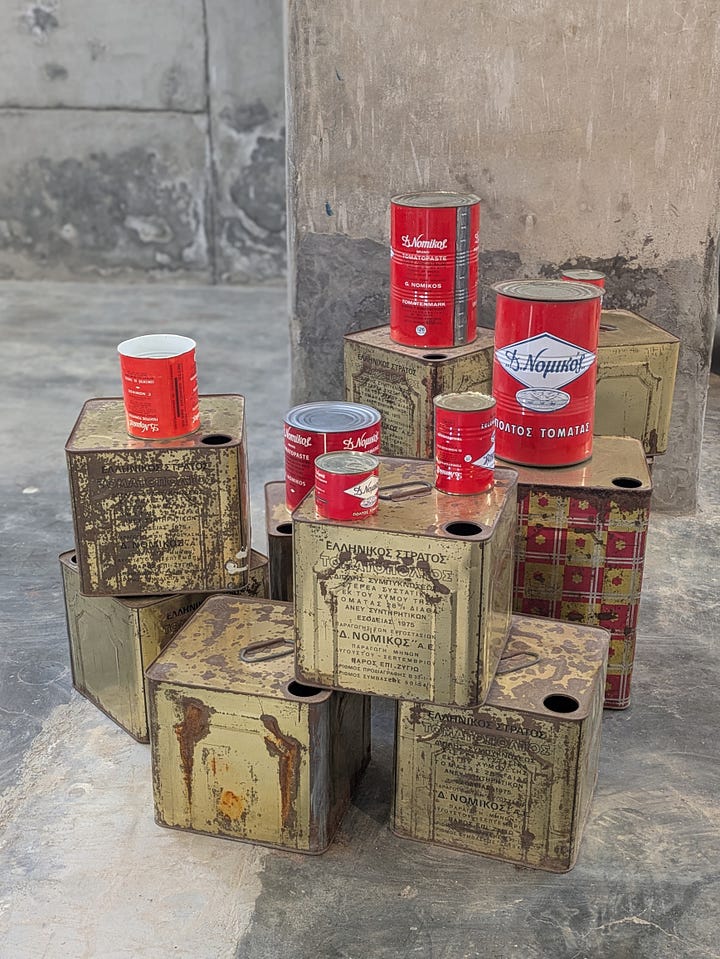

The work was rhythmic, melding spiritual traditions (an annual consecration ceremony in June preceded the start of production) with practicality. The last tomatoes to enter the factory came from Pyrgos, a little inland village, in August. Tomatoes had to be well-washed, graded, cut and pressed to extract their juice and remove seeds. Substandard tomatoes and the processed skins would be returned to farmers for fodder, and seeds saved for planting the following year. Juice was boiled under vacuum to produce paste in a boiler so huge it couldn’t fit onto a boat and had to be sealed and towed from Crete. The paste was then transferred in wagons to be pasteurised and canned in a process that took less than four hours. 3.5 kg of fresh tomatoes are required to make 1 kg of paste. The smallest, roundest tomatoes were pasteurised and canned with their juices. Huge catering cans and tins were loaded onto small boats, which set sail for Piraeus, Thessaloniki and Volos, destined for the nation’s grocers, restaurants and even the Greek Army. Stores would sell a spoonful of paste dolloped onto a square of waxed paper for one drachma.

The tomato industry has prevailed despite the challenges presented by industrialisation, the pressure tourism places on land availability, floods and mudslides (the factory was buried under mud 2.6m high), and a powerful earthquake in 1956. Tomato farming declined, and low yields forced the company to pay triple the price to suppliers, in an attempt to maintain supply and production. At its peak, the factory processed 185 tons over 24 hours, employing 60-75 workers, including many women. In 1950, Santorini’s tomato industry had nine factories located around the island, of which D. Nomikos in Vlychada, built in 1945 by George, son of business owner Dimitrios, was the largest. He included a small unit to make the tin cans used for their products. Before this, Dimitrios had been producing tomato paste since 1915 using pre-industrial technology in Messaria, Santorini, before building more factories across the island for the production of canned tomato products. The museum tells us that forty years ago, thirty processing plants were in operation. Now just four remain. Modernisation has had a huge impact on how tomatoes are processed. The new units can match Vlichada’s entire seasonal output in twelve hours. Despite the company increasing its market share by the 2020s, opening plants in Turkey to supply preservative-free tomato products to Heinz, Marks & Spencer, and Nippon Del Monde among many others, production at Vlychada ended in 1981, and the site was converted to a museum in 2014.

It’s now one of my top ten museums for interest, beauty of design, the quality of the (deceptively simple) displays, technological innovation (holograms of former workers combined with audio and video recordings) and the staff’s friendliness. There’s a shady cafe serving a simple menu that is (obvs) tomato-based including a stellar Bloody Mary rimmed with black volcanic salt expertly mixed by Maria, a tomato chutney served with pickled caper leaves (I have just put up a jar of my own), and tomato paste that is so sweet and luscious it can be — and is — served spread on bread and crackers. Tomatoes grow in the courtyard for visitors to pick and eat; their lusciousness is striking for a fruit whose flesh is considered to be low in moisture. The factory is also home to the Folklore Museum of Santorini, with displays housed in a traditional two-room cave highlighting the work of island cobblers, carpenters, coopers, basket weavers, fishermen and hunters. There’s also lots of information about the island’s printing and press history, and a rich programme of special events including cookery classes.

The museum shop is brilliant; they even have a little labelling machine where you can label cans to take home. I spotted Claire Thompson’s book about tomatoes on sale. We bought cans and jars of paste, canned tomatoes, magnets, and bottles of spiced tomato juice to use in cocktails.

I was conflicted about visiting Santorini, and, post-trip, these feelings have not changed. I was pretty aghast at the behaviour of tourists, some of whom were overheard complaining about locals taking priority on buses, and having to pay tourist tax, and I ended up intervening in the town of Fira when a stream of visitors failed to make way for the very hot and patient local delivery man standing at the side of a tiny lane with a heavy load of bottled water. I physically blocked their way with my arm; I’m not proud of losing my temper. Companies are offering ‘flying dress photography’ which, locals tell me, causes utter havoc in Fira and Oia when entitled influencers block public spaces to have their photos taken. Some companies provide horses for influencers to sit on, skirts flying, and I wondered if the horses ever spook and yeet them into the caldera. I’d pay for a photo of that.

If we must visit Santorini, is it possible to be a ‘less-worse’ tourist? There are a few things you can do:

Avoid Airbnb or VRBO unless you are staying with someone in their property.

Don’t waste water; you don’t need to use the beach showers because the black ‘sand’ brushes off easily. Shower at the hotel. Reuse your towels by drying them off outside in the hot breezy sunshine.

Don’t use public transport during the busiest times when locals are commuting to work (unless you have to catch a flight, etc). When you do use the buses, give priority to islanders. The buses are often full and it is extremely shitty behaviour to expect a seat at the expense of the people who live there.

Don’t wander around Fira or Oia with selfie sticks, backpacks, and full photoshoot equipment, getting in the way and climbing on the house roofs to get that sunset shot. (Yes, this happens, the locals tell me. Tourists even climb onto church roofs.)

I beg you, please do not ride one of the donkeys that are used to transport lazy, selfish tourists up hundreds of steps from Fira’s old port to the rim of the caldera. It is a disgusting, abusive sight.

Spend your time at the museums, galleries, vineyards and microbreweries. Spread your money about; eat and drink at different places. TIP often. Always tip people if you ask to photograph them.

Other recommendations:

Santorini is a dusty, breezy island. It’s in the Cyclades after all. I realised that wearing expensive sunglasses is daft when the wind hurls actual rocks at your face. My lenses will have to be replaced. Ditto outfits: this is not a place for your best, most delicate clothes. Everything gets covered in dust and sunscreen, so maybe reconsider those white dresses.

The tap water is desalinated and non-potable, which isn’t a problem; bottled water is cheap. But it is hell on your hair unless you use bottled water for a final rinse, which is too decadent even for me. Accept that your look will be ‘beach hair’ whether you like it or not. NOTE: If you have fine hair, you’ll spend hours combing out knots unless you tie it back.

Here’s a short video of the Fun Train showing the museum’s chimney and the bay. I enjoyed listening to Don’t Leave Me This Way as we climbed up a hill. It actually was fun; business owners and locals along the way waved to the lovely driver and us, some even blew kisses. Sometimes passengers sing along to the music; I suspect that happens during the evening trips.

This feature in Pellicle by Katie Mather about Tenerife is relevant to my comments about tourism. It’s a really good read.

Absolutely fascinating, what a wonderful thing they have created to preserve this history. The way that you have described how tomatoes are grown are very similar to how I have seen them in central Sicily (also dry farmed out of necessity) -- probably the tastiest I have ever had. Also thank you for writing about overtourism and how to be a better traveler in these places too. Living in Italy, I witness this first hand!

I always remember talking to a German man at a tradeshow and somehow we got talking about holidays. He was telling me "In Santorini there are monkeys who carry your cases up the hill". It took me a good while to realise that just one letter lost in translation gave a very funny scenario!